Honeysuckle Material Investigation and Recognition

Honeysuckle (Lonicera) is flowering bush well known for its fragrance, with some species growing to a height of thirty feet. It is both a native plant and an invasive species in Missouri. The genus Lonicera describes the native tree as well as the more rapidly growing and invasive species: Lonicera maackii and Lonicera morrowii. These species originally came from Asia, and were introduced into America in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. There are one hundred and eighty known species of Lonicera, over one hundred from Asia. Approximately twenty species of Honeysuckle are native to North America, typically grow to a height of ten feet or less, and rarely live beyond 15 years. Since the Asian species are non-native, they grow faster, larger, and are older than native species; partly due to their nature, but also because they have no natural predators, plant or animal.

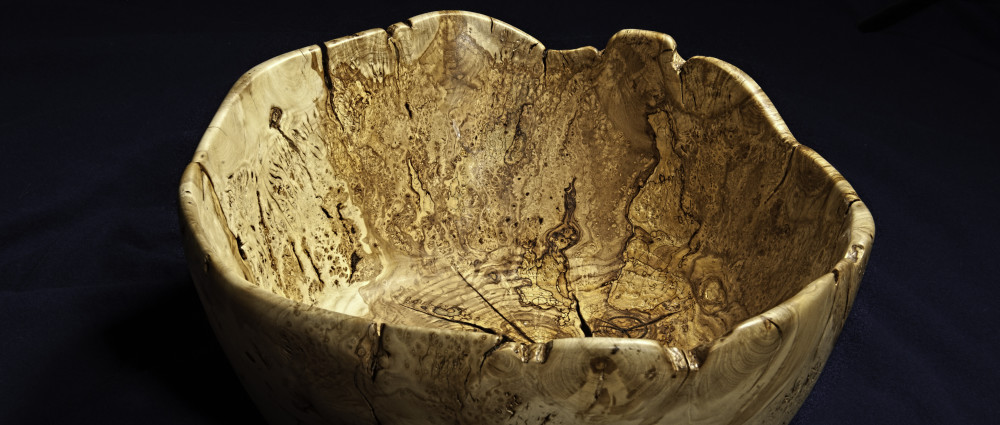

Examining the Honeysuckle, one notices multiple stalks coming from a centralized location. Rather than splaying apart, the roots grow together in one unified mass; commonly referred to as a “root ball.” Over the past few years, I have used larger root balls to make wooden bowls, either by turning them on a lathe or carving “free style” with gouges and a hand grinder. During the past eight weeks, I have attempted an entirely new approach, cutting the root ball in a fashion that results in standard, rectilinear forms.

Honeysuckle is currently an unrecognized wood species by any wood database. I am currently working with Honeysuckle in the hope that it will gain some well-deserved, formal recognition within the woodworking community. As seen in the present display, it has unique and fascinating grain pattern, a good finishing surface, and it lends itself well in many applications. Some of the complications I have faced during the processing of Honeysuckle are related to the ways in which the wood grows and its hardness. The wood grain formation in the Honeysuckle root ball is similar to that found in the burl section of other trees; where there is complete disruption of typical growth patterns, dramatic changes in fiber growth direction, and a highly irregular of grain structure. The grain patterns in the trunks are more typical and linear, but as it transitions into the rootball, the grain quickly transforms into highly complex and non-linear patterns.

Due to the chaotic nature of the grain, the wood loses moisture equally from all the exposed surfaces, which causes many problems in the drying and curing process. If the wood is cut apart and left exposed to low humidity conditions, it begins to warp and crack immediately, and the chunk will eventually become unusable due to this dramatic distortion process. To minimize this problem, I tried many techniques to slow down the water loss process, such as beeswax coating and an experimental treatment technique that I have been developing. This technique consists of soaking the chunks in a solution, part alcohol and part wood sealer, which slows the moisture loss process and reduces shrinkage and cracking.

I also have encountered additional problems while cutting the root balls apart into usable sections. Due to my background in chainsaw sculpting, I first tried to use the chainsaw to cut the root ball into round slabs. The chainsaw was not a good option. The wood was very wet, causing it to warp while cutting, pinching the cutting chain, and the resulting wide saw kerf caused a large amount of wood loss. After I realized that the chainsaw was not the right tool, I then cut the rootballs by hand with a couple of handsaws: a crosscut panel and a traditional carpenter’s bow saw. I hand-sawed five rounds from three root balls, and kept them in five-gallon buckets filled with the alcohol/sealant solution for four days. After soaking them for four days, the wood cracked dramatically less than it did previously. I am continuing to refine this technique, in hopes that it will result in the most stable and high quality product, and eventually prevent cracking completely. Please contact me. Email me at mingersoll@kcai.edu. There are more Honeysuckle images on the woodworking page.